Smoot-Hawley tariffs led to greatly diminished global trade — and, some experts argue, exacerbated the Great Depression.

Article content

President Trump’s support for high tariffs and disdain for free trade harkens back to a much older policy — the Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930.

Article content

Article content

Fans of the movie Ferris Bueller’s Day Off will remember the nasal voice of Ben Stein’s bespectacled economics teacher delivering a droning lecture on Smoot-Hawley. Stein later revealed director John Hughes asked him to ad-lib the bit in an off-camera reading with the students in the classroom, who “thought it was the most boring thing they’d ever heard.”

Advertisement 2

Article content

But Smoot-Hawley is certainly stirring up some buzz today.

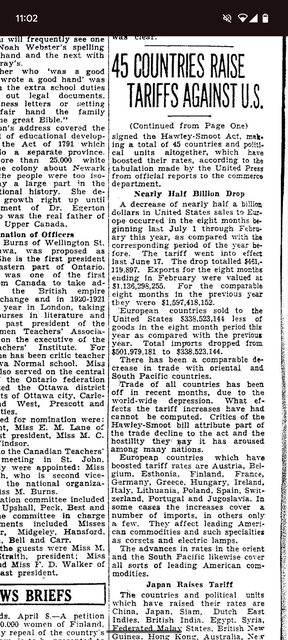

For those unfamiliar with ye old Act, Smoot-Hawley was named for Senator Reed Smoot of Utah, chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, and Representative Willis Hawley of Oregon, chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, who pushed for higher tariffs to protect domestic farmers.

More than 1,000 economists protested the bill to then-United States President Herbert Hoover, but he signed it anyway, which amped up tariffs on foreign exports to the U.S. by about 20 per cent.

The result was that it greatly diminished global trade — and, some experts argue, exacerbated the effects of the Great Depression.

How did the Smoot-Hawley Act come to be?

Robert Bothwell, an emeritus professor of Canadian history at the University of Toronto, said the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was just another example of the “beggar-thy-neighbour” policies favoured by the United States in the 1930s. These policies sought to protect or improve the domestic economy at the expense of other countries.

Bothwell also explained that, at the time, Congress held considerable power and was more involved with tariffs, while the executive branch had a more limited role and typically went along with what Congress wanted.

Article content

Advertisement 3

Article content

In 1930, the Republican party held the White House and Republican protectionists controlled the House Ways and Means Committee, which was advocating for high tariffs.

The bill, originally aimed at protecting American farmers by taxing agricultural imports, soon spiralled out of control, with representatives from various sectors calling for increased protection as well.

How did Canada and other countries respond?

Numerous countries, including Canada, retaliated with tariffs of their own. In 1929, 18 per cent of America’s exports went to Canada, which also accounted for 11 per cent of its imports.

Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King initially matched the Smoot-Hawley tariffs on just 16 products, amounting to 30 per cent of imports from the United States. But when R.B. Bennett took over the Canadian government in 1930, he raised tariffs on American imports even further, while also cutting them on about 270 products from the United Kingdom and its colonies and dominions.

In 1932, Ottawa hosted the British colonies and dominions to discuss the economic downturn and strengthen trade relations between themselves. “It’s a classic trade negotiation, where you’re trading off one concession against another, but the effect is very much to establish an economic sphere where the Americans are not present,” Bothwell explained.

Advertisement 4

Article content

Canada, for example, started selling markedly more of its exports to the United Kingdom and reducing its exports to the United States. Agricultural exports made up about half of Canada’s increased exports to the United Kingdom, according to The Globe archives from 1932.

Between 1929 to 1933, U.S. real GDP plunged nearly 30 per cent, while the unemployment rate spiked at 25 per cent. When the next U.S. election rolled around in 1933, voter sentiment for Republicans had soured.

Franklin D. Roosevelt of the Democratic party took over the presidency and in 1934 signed the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (RTAA), which advocated for strengthened international trade and presidential authority to negotiate reciprocal trade agreements, marking a significant shift in U.S. trade policy. The RTAA also temporarily allowed the president to decrease or increase tariffs by up to 50 per cent of the levels set by Smoot-Hawley in exchange for concessions from other countries.

And ultimately, Bothwell said, the RTAA fostered a new trading relationship with Canada.

“Since 1935, the Canadian-American trading relationship, through a whole variety of arrangements and treaties, has been reciprocal,” he said. “It’s based on negotiation and trade and concessions, but also underneath it, the idea that trade is good, and the ‘beggar thy neighbor’ is a stupid policy in which everybody loses.”

Advertisement 5

Article content

How are things different today?

Bothwell said Trump’s vision for trade is taking the U.S. back to a previous century. But one key difference is that Trump views tariffs as a “weapon of power” rather than protecting local economies, as was the aim of the Smoot-Hawley Act.

Andreas Schotter, a professor of international business at the Ivey Business School, said Trump is using tariffs as a bargaining chip in non-trade issues, such as immigration, currency dominance and geopolitics, “which could lead to more complex and unpredictable retaliations” from other countries.

Schotter noted that during Smoot-Hawley tariffs, the global economy was not as integrated as it is today. “It’s different now, and we have a much more complex and complicated relationship in global trade that includes parts and semi-finished products and so on, where the supply and value chains are cross-border integrated, and in this case, particularly between Canada and the United States.”

He foresees issues in the American manufacturing space in particular, since the U.S.does not have the labour to fill advanced manufacturing roles, especially in the midst of the immigration crackdown.

Advertisement 6

Article content

The effect of Trump’s tariffs would be inflationary and could “absolutely” lead to an economic downturn, Schotter emphasized, adding that it could have economic, political and geopolitical consequences. He predicts the tariffs would accelerate the ongoing decoupling between the U.S. and China, which could pose a major issue for the former since it benefits from global trade.

“We have seen for some years already the reversal (of) a global political economic system, going from a free-trade-for-all system to a fragmented (one),” Schotter said. “This is just a continuation of that on an escalation at the highest level.”

How can Canada respond today?

Bothwell noted that Canada has a much larger economy today than it did in 1930, and therefore stands a better chance of supporting itself through domestic production and consumption.

Foreign Affairs Minister Melanie Joly recently said removing interprovincial trade barriers was going to be part of Canada’s response to Trump’s tariff threat.

Canadian political leaders have also prepared a list of retaliatory tariffs they could implement if the United States goes ahead with its plan for 25 per cent tariffs on Canadian goods.

Advertisement 7

Article content

But unlike in the 1930s, it might be more difficult for Canada to expand its trade relations with other countries to offset the impact. During the early 20th century, Canada still had a fairly strong trade relationship with the United Kingdom: A 1930 trade report shows about $472 million in trade between the two countries, with about $1.4 billion traded between Canada and the U.S., which is about three times as much.

Recommended from Editorial

-

Canadian businesses in U.S. could pay for digital services tax

-

How Trump’s tariff war could hit Canadians’ wallets

-

How far could Trump go using ‘economic force’?

In recent years, trade between Canada and the U.K. was valued at just $47 billion, compared to the over $960 billion traded with the U.S. — 20 times greater.

“We missed a real opportunity to position Canada and Canadian firms on a more global scale,” said Schotter, noting that Canada grew complacent in its trade relationship with the U.S. “Now everybody’s running around like chickens with their heads chopped off, and that’s not a good thing.”

• Email: slouis@postmedia.com

Bookmark our website and support our journalism: Don’t miss the business news you need to know — add financialpost.com to your bookmarks and sign up for our newsletters here.

Article content

Trump’s tariffs echo a failed U.S. trade policy of the past

2025-01-31 16:58:22