Veteran global investor on American exceptionalism, the future of globalization and how Canada became a breakdown nation

Article content

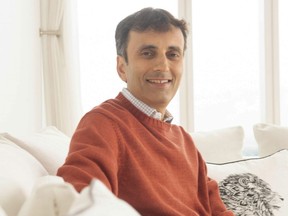

As a veteran global investor, Ruchir Sharma has built a career out of identifying the next winners in emerging markets. But even superstar economies can crumble into “breakdown nations” — a label Sharma recently bestowed on Canada. Sharma is chairman of the investment firm Rockefeller International, founder and chief investment officer of Breakout Capital, a contributing editor to the Financial Times and the author of several books, including “What Went Wrong with Capitalism.” In this Q&A with the Financial Post, Sharma discusses the state of emerging economies, U.S. divergence and what could prompt a Canadian comeback. The interview has been edited and condensed.

Advertisement 2

Article content

Article content

Article content

FP: You published a book called “Breakout Nations” and have also written about comeback nations, but last year you added a new category, breakdown nations, and identified Canada as one. What went wrong for Canada?

RS: If you look at Canada’s per capita income, it’s been a massive laggard since 2010. Across the developed countries, in fact, I don’t know of any other major country where per capita income has done as poorly as Canada’s. Not even the likes of Germany and the U.K., which have otherwise been the poster children for economic trouble around the world in the last 10 to 15 years.

Obviously, the U.S. has been in a league of its own in terms of per capita income increase. But in Canada, the cumulative per capita income increase over the last 15 years has been minuscule. The annual rate in the last decade has been close to zero. That’s one very simple measure as to why Canada has been such a big laggard. Because before the 2008 global financial crisis, at least, Canada’s per capita income was growing in line with that of the U.S.

The divergence has been incredible, and I’d say this is a pretty damning statement on the outgoing prime minister — that he’s presided over practically zero per capita income growth since becoming prime minister. What masks a lot of this is that Canada’s overall economic growth hasn’t been that bad, but that’s mainly due to better demographics, such as population and immigration. At the end of the day, per capita income growth is what really matters to the average Canadian, and that has been quite poor. That’s the principal reason why I included it as a breakdown nation.

Advertisement 3

Article content

The other issue with Canada is the fact that, whatever growth it has achieved has been largely driven either by the government or, in the private sector, by a lot of debt — particularly in the mortgage sector, which raises the issue of financial stability. Canada’s private credit to GDP is one of the largest globally and has increased massively over the last couple of decades. A lot of these mortgages are at variable rates and are getting repriced very fast, unlike in the U.S., where a lot of it tends to be at fixed rates, so any pain from high interest rates is amortized over time. Housing affordability in Canada has obviously been declining very sharply, and that’s an issue.

The only positive for Canada at this stage is the fact that the currency has become cheap, particularly against the U.S. dollar. The prospect of getting a new leader is always good for a country that’s gone through a difficult time, because we find that’s what helps drive economic reforms and some change. And the fact that a lot of people have turned negative on Canada and the narrative now is much better understood. So from a contrarian standpoint, Canada looks a bit better.

Article content

Advertisement 4

Article content

But overall, there can be no debate about the fact that it’s been a breakdown nation, based on simple metrics like per capita income, where its performance has been the worst of any major country in the world over the last decade or so.

FP: What would it take for Canada to become a comeback nation? What are the key things Canada needs to fix?

RS: One thing is that it needs to be a bit preemptive about how it deals with the whole mortgage situation, because you don’t want a mortgage crisis or a debt crisis to happen in Canada. But more than that, I feel that the government has to become much more supportive of investment. You need the private sector to see its animal spirits come back. On the technology front, Canada has been a big laggard because there’s a tech boom going on around the world and Canada really hasn’t shown much prowess on that front.

Those are a couple of things that I see out there. A failure environment for investment. A less interventionist government in terms of that. Reducing its dependence on government spending because, like I said, a lot of the consumption is really driven by the government. Also, building trade relationships outside of the U.S., because it’s hard for nations to become dependent on the U.S., given where the U.S. is going in terms becoming much more of a protectionist nation.

Advertisement 5

Article content

FP: There is a lot of talk about “American exceptionalism” these days, but you called what is happening with the U.S. “the mother of all bubbles” — not just in the stock markets but due to America’s general outperformance relative to the rest of the world. What trends are you seeing in the U.S. that make its dominance unsustainable?

RS: Firstly, let’s just recognize that this has been an incredible period of outperformance for America. You have this great disconnect that’s opened up where America’s share in the global economy is just under 30 per cent, but its share of the global stock markets, if you look at the global MSCI index, is approaching 70 per cent. If America keeps outperforming at this rate, it will practically be the only country in the world to invest in. A lot has to do with the fact that this law of large numbers catches up with America.

There’s a lot of recognition of America’s strengths, and I’ve also been a big fan of America, but I’d say that now, in the last few years, there are a couple of things that really concern me.

One: that a lot of America’s growth, which the world is very impressed with, is being financed by an increased amount of debt. In the U.S., it now takes $2 of government debt to generate $1 of GDP growth. That’s just unprecedented. I know no other country in the world with such math currently. And that’s a function of the fact that America is running a fiscal deficit of about six to seven per cent of GDP — and this is in the middle of an economic recovery. Can you imagine how much that deficit would be if you end up getting a recession? It would blow out to 10 per cent or something. These are very unsustainable finances which are propping up America’s economic growth.

Advertisement 6

Article content

The second thing is that everyone is super impressed with the AI wave and the AI mania in America, but I feel that there’s a bit of a risk here, because we don’t know what the returns on this AI are going to be, and everyone’s just rushing to invest in AI where they can. That’s because the tech prowess is one thing that has led to America doing so well, but the tech prowess is not something that will last and it can also lead to mistakes of hubris, overconfidence and overinvestment.

The other point I’d say is the dollar is now super expensive. On some measures, the dollar is the most overvalued that it’s been since it became a freely floating currency back in the early 1970s. It’s a very expensive currency now, and that’s bound to hit America’s competitiveness. A lot of the returns in America have been turbocharged by the dollar being so strong. When the dollar starts weakening in the next few years, even months, I would expect that the returns elsewhere will look more impressive, and people won’t allocate so much capital to America.

What concerns me is the groupthink that says this can only continue. That under Trump, the dollar’s bound to get stronger, the environment is more business-friendly, so the stock market is bound to go higher. This whole idea that if there’s any place you want to invest in, it’s America. That unidimensional view is what concerns me in the near term.

Advertisement 7

Article content

FP: What’s your outlook for U.S. stocks in 2025 — will the U.S. market continue to outperform this year?

RS: No. I’d be very surprised if the American stock market were to outperform the rest of the world this year, given the path that I’ve explained, given that the concerns could turn more towards the deficits as the year goes by and the fact that the overvaluation is already so significant. Things begin to happen quietly at first, and then they happen suddenly.

This is very short term, but even this month, while the American market has continued to par ahead, the European markets have done even better for the first time in a long time. It could be possible that, very quietly, things are beginning to change. Getting the timing on these things is very difficult, but, just given how bullish sentiment is towards America, it would be very surprising to me if the American stock market outperforms the rest of the world this year.

Q: U.S. President Donald Trump is back in office. Will his policies make America even stronger economically, or cause more problems than they fix?

RS: Firstly, I feel the world is far, far too focused on what Trump’s going to do. Every conversation begins with, “This is what Trump can do, this is what Trump’s impact is going to be.” My feeling is that, a year from now, if you look back, maybe the impact he had wasn’t that great. I guess I’m in that camp, which is the fact that the effect of what he can do or cannot do is possibly being overestimated. Mainly because he gets so much mind space and media share, so we think that this is all that there is.

Advertisement 8

Article content

Even if you look at his first term, things played out a bit differently than what people initially expected, and the contrast is striking. When he first won the election in November 2016, the markets freaked out about what he would do. And then, in 2017, we had a very stable year where the market went steadily up, with very low volatility, and the best performing market in the world during his first term was the MSCI China (Index). Of course, different factors were at work in China. The tech sector was booming, Tencent and Alibaba were emerging as global behemoths.

I’d say that his policy mix can be both good and bad for the market. So far, we have seen the better side, which is that he hasn’t acted on tariffs as yet, so the markets have been relieved by that. On the other hand, he’s talked up things like AI, the business environment, cutting corporate taxes, which have been good for the market and the animal spirits. So I’d say what he’s done has started out on a positive note, undoubtedly because he hasn’t done anything on tariffs, which is the big fear.

But as I said, there are other concerns that could easily come up. If he keeps pushing for more tax cuts without them being funded, concerns about the deficits could come. And we know that the bond vigilantes around the world are getting more active. We’ve seen that from Brazil to the U.K. And then also the fact that if he still does tariffs, that could have some impact on the negative side.

Advertisement 9

Article content

He is obviously an important factor, but not every single investment professional or analyst today thinks that the way to analyze markets is to start by what Trump is going to do. There are multiple factors at work.

FP: Does “America First” and Trump’s more isolationist agenda mean globalization is dead? What does this mean for the breakout nations of the world?

RS: In terms of learning to trade without Trump, most of the fastest growing trade routes in the world today don’t include America anymore. America’s share of global trade is declining, whereas if you look at the share outside of that, it’s been pretty stable. We’ve seen a slowdown in globalization over the last 10 years, for sure, because America has turned more protectionist, and global trade has collapsed everywhere. It’s sort of plateaued. But it’s really America where things are declining. And there have been enough countries in the world where global trade as a share of GDP has gone up significantly — countries like Japan, Italy, Sweden and even the breakout nations like Vietnam, Turkey and Greece.

It’s very much a nuanced picture, but the main picture is that global trade as a share of GDP has been stable around 60 per cent, but within that, America’s share has come down, whereas in many other countries it has in fact gone up. So, because America is turning a bit more inward and more protectionist doesn’t mean that’s the benchmark for what’s happening around the world. A lot of other countries are quietly moving on to increasing bilateral trade, regional trade agreements. And as a result, of the 10 fastest growing trade corridors in the world today, five have a terminus in China and only two have a terminus in the U.S.

Advertisement 10

Article content

FP: You’re a veteran of emerging markets, and you’ve noted that emerging economies are rebuilding their growth lead over developed economies — even the U.S. Why should investors be looking at emerging markets, and what countries or emerging markets are you looking at in 2025?

RS: Emerging markets have done very poorly over the last 10 to 15 years. They had a great decade in the 2000s and after that it’s been quite poor in terms of performance. But, frankly, outside of the U.S., everything has done very poorly. There was a fundamental reason for that, which is that a lot of these emerging markets were paying for the sins of the 2000s, when they had a wild party. They took on too much debt, and then China’s decline has also had a negative impact to some extent — especially for the commodity markets where so much overinvestment had taken place.

But now I think a lot of these emerging economies are hitting an inflection point. Over the next five years, based on the projections, I expect that about 85 per cent of all emerging economies are likely to grow faster than the U.S. That’s a very high number. That’s a number we last saw back in the 2000s. So I think emerging markets are on a bit of a comeback trail. A lot of people have given up on emerging market investing because the last 10 to 15 years have produced no returns, but that’s true, as I said, for most international markets.

Advertisement 11

Article content

Recommended from Editorial

-

Sharma: American exceptionalism is not everything

-

‘Breakdown nations’ like Canada have a lesson for the world

I’ve always liked India because it’s a great place to invest, at least from a stock market perspective, given the fact that there are so many good quality companies in India. Apart from that, there are many other markets that are trading very cheap today. Indonesia, Philippines, Poland, Greece. Argentina is surprising everyone with the kind of reforms that it has taken out, and if it becomes the model for change in Latin America, that could have positive impact on other countries as well, because Latin America has also been undermined by the so-called “pink tide” in socialism. And then you have countries like Vietnam, Malaysia. I think that these are some of the breakout stars that I would point to both for 2025 and the coming years.

• Email: jswitzeroconnor@nationalpost.com

Bookmark our website and support our journalism: Don’t miss the business news you need to know — add financialpost.com to your bookmarks and sign up for our newsletters here.

Article content

How Canada became a ‘Breakdown Nation’: Ruchir Sharma

2025-01-30 19:58:21