Canadian businesses have the opportunity to emerge from this fog of uncertainty with a newfound position of global strength and influence. Joe O’Connor talks to the entrepreneurs saying no to doom and gloom

Article content

Kalid Hedjazi experienced a life-changing moment at a gas station in Detroit in 1993. His uncle Ali was hospitalized in the United States, and Hejazi had driven across the Ambassador Bridge from his home in Windsor, Ont., to visit him. He was distracted and worried sick, but he stopped along the way to get gas and found a sea of sugary delights when he went inside to pay.

Advertisement 2

Article content

Article content

Article content

There were American candy bars, powdered doughnuts, snack cakes, cookies and a slew of other mouthwatering, made-in-the-U.S.A. confections that Hejazi had never come across on the Canadian side of the border.

The entrepreneur from a Lebanese-Canadian immigrant family full of entrepreneurs was, alas, fresh off a setback, having watched the successful Persian rug retail and cleaning shop he ran with two of his brothers become less successful and close. In short, he was on the lookout for the next thing, and he figured American treats were it.

“The thought of importing candy from the United States wasn’t remotely in my mind when I went to Detroit to visit my uncle, but as soon as we saw all that American candy at the gas station, I knew what we were going to do next,” he said.

Article content

Uncle Ali recovered, although he has since passed away, but Hedjazi remains hooked on American junk food and today imports about US$200,000′ worth of treats annually as the owner of Dedicated Marketing Group Ltd., shipping them north from New Jersey to a warehouse he owns in his hometown.

He then loads the candy into a white GMC van and goes on sales tours, selling his wares to convenience store owners in cities across southwestern Ontario. He has known some of his buyers for 30 years. He has also bought and paid off a house and put three children through university on the back of a business now inconveniently at risk of being put out of business by an impulsive American president.

Advertisement 3

Article content

Donald Trump’s 25 per cent tariffs on Canadian imports are on “pause,” but should the détente between trading partners break down, U.S. chocolate is among the items on the Canadian government’s retaliatory tariff hit list.

If there is a trade war, I’ll be one of the casualties

Candy importer Kalid Hedjazi

“If there is a trade war, I’ll be one of the casualties,” the candyman said.

Hedjazi’s survival strategy to date has been to stockpile inventory in advance of any fight. But if the tense days turn into tense weeks and then erupt in March in a tit-for-tat, 25 per cent tariff brawl, he can’t envision a strategic path forward that does not end with his business getting chewed up.

Companies of all sizes that export to the U.S., import from the U.S. or perhaps do both through cross-border operations and, in many cases, have American employees are looking at numbers that don’t add up when, say, that candy bar you have been importing since the early 1990s suddenly costs 25 per cent more than it did the day before.

But if there is a rallying cry to be heard from Bonavista, Nfld., to Vancouver Island, it is that now is not the time to panic.

Within the seeds of a momentarily dormant trade conflict, but with four more years of Trump volatility on deck, is an opportunity for Canadian businesses to calmly take stock of the situation, do some creative thinking and execute a response with future profits and potential new markets in mind.

Advertisement 4

Article content

In other words, it sure might look a little grim out there, but what if Trump’s tariff posturing produces an end where Canadian businesses emerge from the fog of uncertainty with a newfound position of global strength and influence?

“In this moment, the last thing you want to do as a business leader is freak out and start running around like a chicken with its head cut off,” Andreas Schotter, an international business professor at Western University’s Ivey Business School, said. “You need to be pragmatic, strategic and proactive.”

On the pragmatic front, he said Canadian businesses should identify their core market. If, for example, you are a widget maker with a factory in Ontario, and American consumers buy 90 per cent of your widgets, the company could look at shifting “certain activities” to the U.S., but also be wary of overallocating resources there.

A widget tariff that, in theory, takes effect in March, or any other time Trump plucks from the air, could be abandoned the next day. Long term, Schotter said every Canadian company must heed the wake-up call of an unneighbourly U.S. government that appears comfortable wielding an economic club to get whatever it wants and be looking for opportunities to sell their widgets elsewhere.

Advertisement 5

Article content

Plowing ahead

In the Canadian tech universe, Jim Estill is somewhat of a living legend and a mentor to many successful whiz kids. The 67-year-old’s first business venture in the 1980s was selling computers out of the trunk of a brown 1971 Oldsmobile Cutlass while on the road to building a multimillion-dollar company. He later became one of the founding board members of Research In Motion Ltd., a.k.a. BlackBerry Ltd.

Lately, though, he has been selling bar fridges and other appliances as the chief executive (and owner) of Guelph, Ont.-based Danby Products Ltd., which has been around since 1947. He also owns Arctic Snowplows, a Canadian company that has been around since the 1960s.

“Everyone thinks the sky is falling, but I’m old enough to know the sky’s not falling — this is just a stubbed toe — and we’re going to get over it, and everything is going to be fine,” he said.

Article content

One of the truisms of being a manufacturer is that it is impossible to pivot operations on a dime. If, for example, Estill decided to come out with a new line of bar fridges, they would not appear in stores for at least another year.

The point is that retooling a factory, designing a new product, unspooling a marketing campaign, adjusting a supply chain and the like all require time, money and advance planning, and he is not about to make any rash decisions.

Advertisement 6

Article content

However, one decision he has made is to skip the appliance industry’s major Las Vegas trade show this year and head to a show in Germany instead to showcase Danby’s products to potential new customers in Europe.

“Companies are going to seek out other markets,” he said. “But all of that takes a long, long time; it doesn’t happen quickly, right?”

If you are a loyal Canadian, you are even more loyal today than you were a year ago

Jim Estill, owner of Danby Products Ltd. and Arctic Snowplows

Estill has also spent a lot of time thinking about the Canadian psyche. It is not an exaggeration to say Canadians, lovers of peace, order and good government, aren’t too happy about what the U.S. president has been up to, and that unhappiness may come to inform the choices we make as consumers.

“If you are a loyal Canadian, you are even more loyal today than you were a year ago,” he said.

Estill’s marketing department has designed a run of 50,000 red “Proudly Canadian” stickers that the boss intends to slap on Danby products sold in Canada. All things being equal on price, he is willing to bet that the guy in the big-box store contemplating buying a new bar fridge for Christmas might be inclined to pick his company’s product over something from the U.S. or someplace else.

Article content

As for snowplows, manufacturing involves bending, forming and welding steel. Arctic Snowplows has an American consumer base that Estill wholly expects would be killed off in a trade war. If that were to occur, he would wind down his American operations and concentrate his sales efforts on the Canadian market, but also look to identify American metal products — aside from plows — that could be subject to retaliatory Canadian tariffs, and then start making them in his snowplow factory in London, Ont.

Advertisement 7

Article content

“I’m going to be looking at what has ‘Made in USA’ on it and saying, ‘Well, can I make that here in Canada?’” he said. “What is happening is not all doom and gloom — it is change — and change can invite opportunity.”

Opportunity knocks

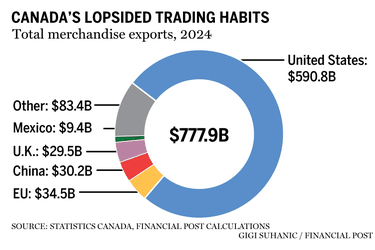

What is happening now might also encourage Canadian companies to finally embrace some healthier trade habits. The numbers tell the story. In 2024, the narrative was that Canada sent $590.8 billion in exports to the U.S., or 76 per cent of the country’s total exports. The second-most popular destination for Canadian stuff was the European Union at $34.5 billion, or 4.4 per cent of total exports.

Do the arithmetic and the value gap between our No. 1 trading partner and the runner-up was a whopping $556.3 billion.

Canadian exporters’ dependence on the U.S. is not new, and it can be explained by a variety of factors, such as proximity to market, a shared language, similar legal systems and a long, fruitful history of free trade.

There is also the added perk for those sending whatever it happens to be south (oil, agricultural products, auto parts, consumer goods) that the U.S. is an affluent society with conspicuous consumption as a near-inborn trait among its citizenry. Americans, as do Canadians, love accumulating stuff, and there just so happens to be a whole lot of them — approximately 341 million at last count.

Advertisement 8

Article content

“The idea that 75 per cent of our exports go to the United States is a big, big problem, but it is not a new problem,” Walid Hejazi, an economics professor at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, said.

In case you are wondering, Hejazi is related to Windsor’s candyman. He grew up beating his older brother at pool and card games, and helped him out of a jam related to some powdered doughnuts from Michigan in the early days of his sibling’s import business.

“We had the doughnuts in Windsor in a big cube van, but they didn’t have any French-English labels on them, so we had to print our own labels,” he said.

The kid brother grew up to be an economist/academic and he recalls testifying before a 2017 Senate committee on free trade, where he sketched out a cautionary tale of Canada’s dependence on the U.S.

“I remember I asked the question, ‘Whose fault is it that the decision of one man — that man being Donald Trump — could impact the prosperity of 10 million Canadians?’” he said. “And it was a rhetorical question, but it is Canada’s fault, because the first rule of business is you don’t put all of your eggs in one basket.”

Nearly a decade after Hejazi asked his question, Canada’s eggs are largely still in one basket, which is at risk of breaking. But here’s the good news, he said. Canada is a signatory to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal that includes Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia, Australia, Chile and Peru, among others. All told, it’s a consumer marketplace rivalling that of the U.S.

Advertisement 9

Article content

Canada also has a free trade deal with the European Union and, notwithstanding the unpopularity of the current Liberal government in public polling, the federal government has been proactive in executing a series of so-called Team Canada trade missions over the past several years. The next mission is headed to Australia later this month after previous stops in Japan, the Republic of Korea, Malaysia and more.

The aim of each mission is to connect Canadian companies with potential trade partners, and the mission statement for Australia is to build relationships between Canadian agrifood/agritech, mining equipment and clean, information and communications technology companies and Australian buyers.

“Canada has got a great brand abroad,” Dan Kiselbach, a global trade expert at Miller Thomson LLP and a frequent flier on the Team Canada trips whose bags will soon be packed for Australia, said. “I’ve learned a lot on these trips about the need overseas for Canadian food and agriculture technology, and energy — and the whole raft of technology— and I have also learned that there’s a great desire to do business with Canada. We just have to spend the time fostering those relationships.”

Advertisement 10

Article content

Hejazi’s research suggests that one of the impediments to weaning Canadian exporters off the U.S. is cultural impatience. Canadians might be stereotypically polite, but CEOs are ultimately bottom-line driven. They want deals to get done. A Canadian company negotiating with an American company begins with the parties already at “third base,” he said.

Put simply, we know each other and speak the same language. Recognizing that a Japanese senior executive is culturally distinct from the back-slapping Texan you have been dealing with for the past 15 years, and that getting to know them may take a bit more time and a much bigger bite out of the expense account are keys.

“When you start to go to less traditional, more distant markets, you need to build trust,” Hejazi said. “Canadian companies need to get out there because it is a big world.”

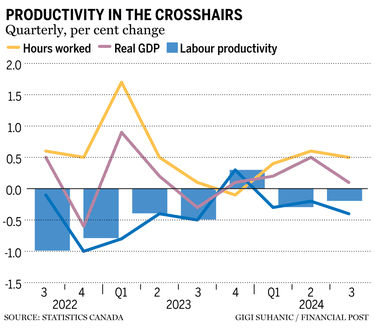

What Canada also needs to do, he said, is boost its productivity. Canada may have a great brand internationally, but the country is 30 per cent less productive than the U.S. and 10 per cent less productive than Australia, according to a Royal Bank of Canada report. To get ahead, Canadians are going to have to hustle.

Unfortunately, the track to success is tilted to the U.S. for the whole host of reasons that got Canada into its current, trade-dependent mess in the first place.

Advertisement 11

Article content

Dave Caputo, another tech player, has a pet peeve related to the waste generated by the drywall industry dating back to his youth in northern Ontario. It is a beef, following the sale of Sandvine Corp., which he founded and sold for $444 million in 2017, that he acted upon by becoming part-owner and chief executive of Trusscore Inc., a sustainable building material startup headquartered in Palmerston, Ont.

One of the growing trends among house-proud North Americans is renovating their garages, a phenomenon that gathered steam during the pandemic when dusty old spaces were transformed into home gyms and offices. Fixing up the garage today is a multi-billion-dollar industry.

“We have seen significant growth primarily driven by the residential uses of our product, particularly in the garage space,” Caputo said.

The company has revenues in the $55-$60-million range, he said, 200 Canadian employees and a small team of American-based sales staff since 80 per cent of Trusscore’s made-in-Canada product is purchased in the U.S.

“The reality is there is no market like the United States,” Caputo said. “It has a high population and relative wealth, compared to almost every country in the world, and they are just a great customer to have next door.”

Advertisement 12

Article content

Article content

Should Trump close the door, or at least make it prohibitively expensive for Canadian manufacturers to get products through the door and remain competitive, he could look to grow sales in Latin America. He has also been having discussions with his American customers about stocking up on inventory and with his American competitors about working together should tariffs be put in place.

Caputo can imagine a scenario where his factory in Calgary makes formerly U.S.-made products sold in Canada that would otherwise be subject to counter-tariffs, while an American factory makes his stuff. Both sides, if not thrive, at least live to fight another day while they seek out long-term solutions.

But his hope is that all the worst-case-scenario planning he has been doing is simply an exercise in worst-case-scenario planning and that “reasonableness” prevails.

“We used to be both proud, Americans and Canadians, that we had the largest unprotected border in the world, but now it seems like having an unprotected border is something terrible,” he said. “But what does an unprotected border mean? It means that we trust each other, that we share the same values, that we have the rule of law and that a deal is a deal.”

Advertisement 13

Article content

The deal he is referring to is the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, which replaced the North American Free Trade Agreement struck between the three countries that came into effect in 1994 — six years after an earlier free trade agreement negotiated by Ronald Reagan and Brian Mulroney was reached between Canada and the U.S.

But, as it turns out, a trade deal is only as good as the people in charge of it, and the uncertainty over what Trump will or will not do come March comes with a cost.

For example, Estill has been planning a $2.5-million renovation of a plant in London, but the plan is now on hold. Postponing the work has meant the trades who would otherwise be beavering away at the job are not getting paid.

“If the roofer doesn’t get paid, then the roofer doesn’t go for dinner at the restaurant, and if they don’t go out to dinner, they don’t support the waitress, and then the waitress doesn’t have the money to buy my bar fridge,” he said. “That’s what the economy is all about. The uncertain environment weakens the economy.”

In Windsor, Hedjazi has been trying to find the strength to imagine himself not being in the candy business and what he might do next. He doesn’t have any debts, and he still has plenty of energy, so he’s not ready to retire. His neighbours are likewise left wondering what happens next. Two of them work in the auto industry, a third exports produce to Michigan and a fourth has his own cabinetry business with warehouses on both sides of the border.

Advertisement 14

Article content

Their conversations used to be about the weather and sports, but now it’s about unemployment, tariff threats, Trump and his portrayal of Canada as a refuge for fentanyl makers and illegal immigrants itching to sneak their way into the U.S.

“My hope is not so different than any other Canadian: that Trump is bluffing,” Hedjazi said. “Canada has stood with the Americans on so many issues, and for Trump to be threatening tariffs, in my personal view, is disloyal to Canada. I just hope there is somebody who can talk some common sense into the man’s head.”

• Email: joconnor@postmedia.com

Bookmark our website and support our journalism: Don’t miss the business news you need to know — add financialpost.com to your bookmarks and sign up for our newsletters here.

Article content

How Canadians can profit from Donald Trump’s trade war

2025-02-07 11:08:28