Just a few years ago the 40-something WE Charity co-founder was on the ropes thanks to a political scandal and old Rugby injury. Today the committed ‘biohacker’ feels like he’s 25 again

Article content

Marc Kielburger describes his old injury in aching detail. The first thing that came to mind upon hearing the sickening “pop,” he said, was a desperate hope that it had not come from his body and that the twisted mess of an ankle at the bottom of a pile of high school rugby players, circa 1994, did not belong to him.

Article content

Article content

But, alas, it did, and any plans the teenaged Kielburger had of cutting a rug at school dances were replaced by crutches and seven months in a cast, followed by several months of physiotherapy and then, perhaps counterintuitively, by a return to the rugby pitch as an undergraduate at Harvard University and later as a law student at Oxford University in England.

Advertisement 2

Article content

His college athletic career can be divided into two halves: him playing and him sitting on the bench, icing the left ankle that he repeatedly reinjured. A pain that was bad in his 20s would grow exponentially worse, such that by the time he hit 40, he and his wife Roxanne Joyal shared a running joke that they would be skipping to the front of the lines at airports and museums in another 20 years because he would be rolling through them in a wheelchair.

Of course, Kielburger had other ideas, but so did the ankle, which would blow up into a swollen mess whenever he spent too much time on his feet. Workouts were sheer agony. Physiotherapy did not help, nor did the random medical therapies and supposed miracle elixirs he ordered off late-night television infomercials.

“I tried everything, everything, everything,” he said.

Article content

Compounding the chronic physical discomfort was the psychological pummelling he absorbed in 2020 after WE Charity, the outfit he and his younger brother Craig co-founded in 1995, unravelled in spectacular fashion during parliamentary committee questioning around how the organization had been awarded a $43-million untendered government contract to administer a $500-million-plus student service grant program.

Advertisement 3

Article content

The brothers were never found to have done anything wrong, but their self-defence during the hearings registered with a giant thud among the public. In other words, the so-called good guys, the same guys behind the WE Day events that packed arenas with screamingly enthusiastic, volunteer-minded teens, came out looking pretty bad, and the economics of operating a charity during the pandemic coupled with the optics of being involved in a government scandal led WE Charity to wind down its Canadian operations.

“Between the ankle and the politics, I was a complete wreck,” Kielburger said. “I was 50 pounds heavier. I wasn’t sleeping. I couldn’t move.”

Between the ankle and the politics, I was a complete wreck. I was 50 pounds heavier. I wasn’t sleeping. I couldn’t move

Marc Kielburger

The former college rugby player had arrived at a midlife crisis, an inflection point that can lead an afflicted individual down the path, say, to a new sports car, a second marriage, a bad hair dye job and the sudden uptake of cool new hobbies such as kiteboarding. In Kielburger’s case, it led to a private medical clinic in San Jose, Costa Rica, where he has undergone multiple stem cell injections on his ruined ankle — a treatment that has not been approved in Canada or the United States — that cost him $8,000 to $14,000 a pop.

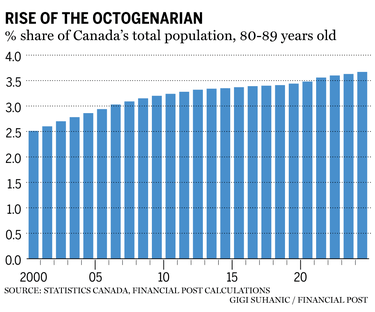

His pursuit of a fix is part of a much broader, complex and lucrative global health and wellness picture that plays on the fact we are all getting older and we are all going to die, but an increasing majority of Westerners aren’t going to die until they are well into their 80s or beyond.

Advertisement 4

Article content

How we choose to live today has massive financial implications for tomorrow, and is creating a longevity economy that is worth trillions of dollars and touches upon everything from Kielburger’s trips to Costa Rica to the average 50-year-old’s decision to start taking those vitamins their doctor keeps recommending and pick up some kale at the grocery store, and to a 65-year-old’s decision to postpone retirement for a few years because they don’t want to quit.

“When people talk about artificial intelligence and climate change, it provokes a really heated emotional and intellectual debate, and lots of talk about radical adaptation and adjustment, and how we should respond to bring out the best and not the worst,” Andrew Scott, an economics professor at the London Business School and author of The Longevity Imperative, said.

“But when it comes to an aging society, we, literally, barely get beyond talking about adult diapers and care, but there’s a lot more radical adaptation and adjustment we can do to make the most of the longer lives that we’ve got. Aging is malleable.”

Older, wiser, better

Aging commonly gets portrayed as a ticking financial time bomb in a narrative that goes something like this: people are having fewer children; boomers are getting old; older folks incur ruinous health-care costs; and pensions are top-heavy with seniors as it is and there are not enough young workers moving up the line to continue funding them. It all spells trouble ahead.

Advertisement 5

Article content

But what if the aging population isn’t a landmine, but a shiny new engine for economic growth? Scott crunched the numbers using data from the U.S. and discovered that slowing down the aging process and compressing morbidity — the amount of time an individual is ill at the end of their life — would be worth US$38 trillion a year to the American economy. The economic benefit of targeting aging and improving individual health could potentially have more impact than eradicating individual diseases.

Kielburger appears to have internalized this message. He has also dabbled in “plasma exchanges” in Costa Rica, which are akin to an oil change, only for blood. Slightly less intense sounding is a daily routine at his home in Toronto that begins when the 47-year-old rolls out of bed at 4:15 a.m. and into a hyperbaric chamber for 30 minutes.

Article content

He then meditates and communes with Daisy, the family’s 120-pound Bernese mountain dog, in order to ground himself emotionally. There is a smoothie full of stuff most humans have never heard of to be drunk; a stroll down to Lake Ontario to revel in dawn’s earliest glow; a breakfast of two avocados, four eggs (sunny side up), walnuts and a pint of organic blueberries; and an intense workout followed by a cold plunge and a bit of family time with his wife and two daughters.

Advertisement 6

Article content

By 8:15 a.m., Kielburger is ready to work, and if what he has been up to lately sure sounds like a lot of work and a lot of money, rest assured he is not alone in his convictions. Instead, he belongs to a much broader community of longevity chasers known as “biohackers,” individuals who are looking to beat Father Time, or at least stave off the inexorable decline, by any means necessary.

That includes ingesting a tasting menu’s worth of supplements, eating special diets and undertaking medical treatments — many of which are experimental, decidedly thin on scientific proof and lacking in North American regulatory approval — in the hopes of extending their health span, defined not by a finite, dead-and-buried age, but by the number of years they live without spiralling into a decline that is costly to the health-care system and themselves.

“I’m treating myself to a certain degree like a guinea pig,” Kielburger said.

I’m treating myself to a certain degree like a guinea pig

Marc Kielburger

Pursuing a long life has not been an inexpensive undertaking, and it’s up for debate whether the guy with the bad ankle emerges as a modern-day Frankenstein or is truly onto something. But at this moment, Kielburger can report that he feels as though he is 25 again and can now balance on one foot, supported pain-free by his historically troublesome joint, and repeatedly jump four feet in the air and land on a board during intense workouts without missing a step. The sound body lives in harmony with a clear mind. In short, the man feels like a million bucks.

Advertisement 7

Article content

“Right now, I’m just trying to learn as much as I can and to be open to where the world takes me,” he said on the eve of attending the world’s largest anti-aging conference at the Venetian and Palazzo Resort in Las Vegas in mid-December.

Joining Kielburger there was Dr. Tim Cook, formerly and, as he puts it, somewhat “tediously” known as “Captain Cook” during his years in the Canadian Armed Forces.

His patients included two governors general. The first, Romeo LeBlanc, was incredibly “nice,” but incredibly bad at following doctor’s orders. The second, Adrienne Clarkson, proved better at following rules, although the professional path Cook ultimately pursued led him away from the army to a position and a good paycheque at a big hospital in downtown Toronto.

Article content

It was there that he experienced a midlife crisis of his own. He had the job, money, cars, house, wife and kids and all the material trappings of success, but he also had the soul-crushing realization that he hated caring for the sickest of the sick, since they generally wound up in the hospital because they had spent the bulk of their lives eating all the wrong foods and doing all the wrong things.

“I was looking after people who wouldn’t have been in the hospital if they had done something differently 30 years before,” he said.

Advertisement 8

Article content

As a result, Cook quit and opened a private practice about 10 years ago within walking distance of one of Toronto’s wealthiest enclaves. His patients there refer to him as Dr. Tim, and about half of them arrive at his door suffering from chronic Lyme disease or some other toxic infection-related ailment, a nod to his training as a tropical disease specialist, while the other half come with a more existential purpose in mind: longevity, a nod to his professional and personal interest in biohacking.

The bulk of this second group are bankers, equity investors and otherwise high-net-worth types who, depending on what “longevity package” they purchase, pay anywhere from $5,000 for an introductory six-month course to $23,000 per year for the “Olympian” treatment.

Dollar spent, another year earned

These so-called Olympians work one-on-one with Cook, as well as with a nutritionist and a naturopath. They undergo a battery of tests, including the DunedinPACE, that quantify the biological speed at which one is aging. The lower your score, the rosier your future outlook.

Diets are personalized, as are vitamin doses and supplement needs. Every six months, Cook repeats the aging test, so patients can track their scores and get a sense of just how far over the horizon the Grim Reaper might be.

Advertisement 9

Article content

“These people are all about performance management because they mostly come from the business world and they understand the value of numbers,” he said. “And if they see that their numbers are getting better, that their pace of aging is going down, then they’ll say to themselves, ‘I’m going to keep doing this.’”

If being an Olympian sounds too expensive for your tastes, fear not. Cook said you don’t need to spend a mint to enhance your longevity prospects.

For the more budget-conscious, he recommends investing in a sleep mask and a blackout curtain, having a purpose in life, walking outside in the fresh air and sunshine, taking vitamin D, particularly if you live in northern climes, meditating daily, drastically cutting back on carbohydrates, engaging in meaningful relationships and avoiding isolation at all costs since being lonely is the “new smoking.”

These people are all about performance management … and they understand the value of numbers

Dr. Tim Cook, longevity medicine specialist

On a macroeconomic level, Cook believes policymakers should be taxing cigarettes, fast food, sugar-soaked snacks and processed victuals beyond the average consumer’s reach, and perhaps subsidizing, say, broccoli so that when convenience food becomes inconveniently expensive, the nutrient-packed options will emerge as the grab-and-go choice.

Advertisement 10

Article content

His other key piece of advice is to “stay alive” because the research around gene editing and stem cells suggests a day may come when some brilliant scientist figures out how to shut off the human aging genes and reset our biological clocks to the fountain of one’s youth.

“This is not science fiction,” Cook said.

The biohackers and boutique longevity clinic crowd represent a small subset of a more astonishing truth. For thousands of years, human beings were remarkably adept at dying young. Longevity wasn’t a huge conversation piece when being pursued by a sabre-toothed cat or facing an enemy with a very long, very pointy spear.

In the much less distant past, the average Swede who was 20 years old in 1851 stood a 20 per cent chance of making it to 80. One hundred years later, that same Swede at 20 had a 30 per cent chance of reaching 80. The odds today of becoming an octogenarian are 80 per cent.

“What’s changed is that now the majority of people can expect to become old, where for most of human history, only a few people got old,” Scott said.

The professor is not a biohacker, but he doesn’t harbour any ill feeling towards those that partake in “unproven” treatments. In his view, it is each to their own. But what concerns him from a social perspective is that the bid to achieve “radical life extension” misses out on the more fundamental challenge of “compressing morbidity” on a mass scale.

Advertisement 11

Article content

If a bunch of us are destined to hit 80, 90 and beyond, without saddling Western economies, Canada included, with untenable health-care costs, then the goal should be to reduce the amount of time we spend being sick at the end of our lives. Healthy aging isn’t simply a luxury; there is big money at stake, but the buyer need beware.

June Cotte isn’t shy about sharing her age, nor is the 56-year-old marketing professor at Ivey Business School in London, Ont., averse to offering her take on human nature.

“I think health and wellness is one of those areas where we’re motivated to want to believe promises that might be a bit hyperbolic because what we’re talking about is dying,” she said.

65 is the new 40

As for the living, Cotte said it is critical when thinking about the “longevity economy” to dispense with the Freedom 55 retirement dream and start with the premise that people who are living longer are going to want to work longer “because who wants to retire and sit around for 30 years?”

Older workers can still be productive. They still consume and they tend to have more money on hand to spend than cash-strapped 30-somethings carrying a mortgage.

This bodes well for the aforementioned wellness economy, which encompasses everything from Cook’s personalized medicine to spa treatments to public health prevention initiatives, and contributed about US$6.3 trillion to the global economy in 2023, according to the Global Wellness Institute. That number could hit US$9 trillion by 2028.

Advertisement 12

Article content

We’re living longer, we’re going to want to be healthier, and that’s where a lot of opportunity is

Andrew Scott, London Business School, author of The Longevity Imperative

“We’re living longer, we’re going to want to be healthier, and that’s where a lot of opportunity is, and I think the broader health sector is going to explode,” Scott said from England.

Another outcome Cotte foresees is a boom in higher education, not among the retirees who want to learn Spanish, but from an aging workforce wanting to maintain its edge. People will want to be proficient in new technologies and possibly even pivot careers at 60 and beyond, armed with that precious advantage only age can provide: experience.

These older workers will want products — not adult diapers, but phones, gadgets, cars, sneakers, you name it — that embrace (and profit) from the recognition that a 70-year-old may not possess the same tastes as a 25-year-old, but they will still want items that are both functional, designed for an older cohort, and look cool.

If people are living longer, their finances should also be positioned to survive along with them, which heralds a new age of innovation in financial products and more work for the wealth management industry.

Of course, not all jobs involve sitting at a desk. There aren’t many 75-year-old construction workers. But a 55-year-old worker, if we accept they have a shot at living to 95, could have their skills and experience repurposed to a less physically taxing job that preserves their bodies and keeps them plugging away for another 10 to 15 years.

Advertisement 13

Article content

Scott refers to this scenario of constant reinvention and relevance as the “evergreen economy.” A key aspect of achieving it plays into what some biohackers are up to, which is a radical repositioning of health-care systems from managing disease and decay to prevention.

“There’s a whole bunch of changes we have to make because for the first time ever, we can expect to live into our 80s and 90s, and so we have to create new ways of living,” he said. “If we don’t, then we’ll end up being 80 or 90 and in bad health and without enough money, without a sense of purpose and being excluded, and all the other negative things that we worry about associated with getting old.”

Article content

Kielburger, for one, does not intend on getting old without a fight. His personality is such that when he gets into something, he gets all the way into it. In high school, it was public speaking; around the house, it has been gardening.

His personal health choices are more extreme and experimental than most, but he believes he can either pay for it now or pay for it later. Three years ago, his body was a wreck. The Canadian arm of his charity had imploded. His reputation had taken a hit; he was stressed and convinced he was destined for a wheelchair and an expensive remodelling of his home to allow him to remain in it.

Advertisement 14

Article content

In a way, he saw in himself what he was seeing happen with his parents, Fred, now 84, and Theresa, 81, who weren’t model stewards of their health, so their health-care costs are skyrocketing. Their eldest son lives a block and a half away, and he has overhauled his father’s diet, and has him working out with a personal trainer and using a hyperbaric chamber because “cancer hates oxygen.”

Kielburger, meanwhile, has come up for air after going through a rough patch and co-written a new book with his brother Craig and Martin Luther King III and his wife Andrea Waters King.

What Is My Legacy? is about living lives “larger than ourselves” in search of that most elusive thing: fulfillment, according to a synopsis of the book. It sounds a bit hokey and is geared to the self-help audience, but Kielburger is irrepressibly earnest in conversation and is not above offering dietary tips about the value of having oatmeal for breakfast and other things.

Whatever is on the menu, it is bound to be a lot less expensive than jetting off to Costa Rica for stem cell treatments. On that front, he has no regrets, at least not yet, and he has even returned to the sport that put him on the road to physical ruin and rebirth as a biohacker in the first place.

“I have been playing rugby and I’ve got my daughter playing a little bit, too,” he said. “I’m trying to keep it pretty tame and avoid the scrums; I’m like, ‘OK, you look like you’re going to hit me really hard, so why don’t you just take the ball?’”

• Email: joconnor@postmedia.com

Bookmark our website and support our journalism: Don’t miss the business news you need to know — add financialpost.com to your bookmarks and sign up for our newsletters here.

Article content

How Canada’s aging society can be a win for the economy

2025-01-02 14:49:25